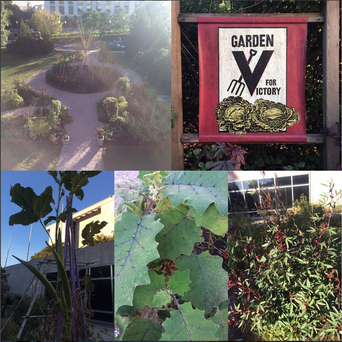

Writing about presidents, politics, and gardens for the American public

In case you've been missing out on some of the best historical writing out there today, you should be sure to check out Made by History, a column dedicated to bringing history to bear upon current events at the Washington Post. Since August 2017, they've been busy publishing brief takes from brilliant historians on a wide variety of topics. Personal favorites include:

- "Good Corporate Citizenship Won't End Racism: The NFL Must Do More" by Jessica Levy,

- The dirty (and racist) origins of Donald Trump’s anti-immigrant slur: How the connection between race and waste shapes not only slurs but policy and economics by Carl Zimring,

- The Real Scandal at the EPA? It's not keeping us safe by Frederick Rowe Davis.

- Ida B. Wells Offere the Solution to Police Violence More Than 100 Years Ago The By Keisha N. Blain

RSS Feed

RSS Feed