[Update available here: The Row Verdict.]

| Without exception, every Victory Garden pamphlet suggests straight rows -- often even emphasizing that they should run lengthwise, rather than across the short side -- so rows it was. The primary reason for running rows lengthwise is that when using animals or machinery, as in large-scale agricultural operations, longer rows means fewer turns at the end of every row. A particularly fortuitous feature of our garden plot is that running our rows lengthwise also meant running the rows North-South. This maximizes sunlight for growing plants, who then have equal access to Southern sun exposure. [If you live in the Northern Hemisphere, the directions that receive the most sunlight to least sunlight, in order, are: South, West, East, North.] Accordingly, we also oriented our plan so that the tallest plants (tomatoes) are to the East of the other rows, to keep them from shading out smaller neighbors like spinach or radishes. | "Plant the garden in long straight rows far enough apart to cultivate with a team and a field cultivator. [...] A garden like this will give the largest returns with the smallest amount of hand labor." |

- The rows situation has already made accessing all the vegetables to plant seeds very difficult, since the plans from 1942 do not include room for footpaths (which would be ridiculously space inefficient). As it stands, we've been treading pretty close to our plant seeds, and likely compacting the soil much more than ideal pretty close to their roots.

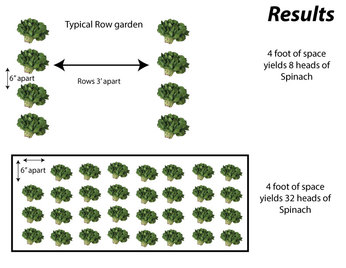

- When you plant only in a single row, you aren't planting as space-efficiently as you could be. {See picture to side.} This already profoundly bugs me, especially given the extreme rhetoric about the overarching importance of maximizing production.

- Weed control. When you plant in a bed style, the plants are close enough to provide a more or less complete canopy of leads above the soil. The labor of weeding comes down to almost zero once the plants start adding on leaves. With rows, there will always be expanses of space between the rows, just waiting for weeds to sprout up. This task has already begun, and is the largest time-suck in this period where all the rows are planted, but not all the plants need harvesting, suckering, or other tending yet.

Speaking of weed control ... the great unending task begins. Personally, I find weeding strangely satisfying and therapeutic. Next to actually eating the produce the garden, my favorite task is killing the myriad plants that pop up. And efficiency is my last concern. Standard garden advice is to simply use a hand cultivator (illustrated instructions here, courtesy midwestgardeningtips.com). However, I get really into the visceral pleasure of yanking plants by hand, individually and painstakingly. While using a hand-cultivator would take a mere fraction of the time, I almost always opt for hand-weeding ... and then spend an hour longer in the garden than I had planned on. (#worstvictorygardenerever.) Am I the only one who feels this way?

In closing, I just have to brag about the back bed off our porch. It's an additional project, where we'll be putting mostly sprawling squash vines. (I have yet to see such space-intensive plants recommended for World War II gardeners.) The bed was almost pure grass and weeds until my amazing partner put in many hours breaking it up while I was out of town last weekend. I can't wait to post an 'after' picture at the end of the summer...

RSS Feed

RSS Feed