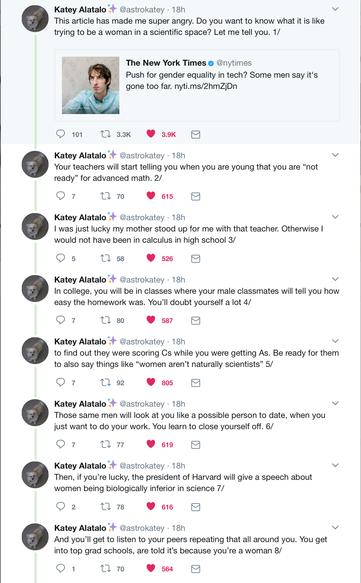

Please read the entire thread by the awarding-winning astrophysicist (and frequent target of toxic masculinity on the internet), Dr. Katey Alatalo. Link in pic.

Please read the entire thread by the awarding-winning astrophysicist (and frequent target of toxic masculinity on the internet), Dr. Katey Alatalo. Link in pic. I was a grade-grubbing teacher-pleaser and internalized this 'failure' deeply. By high school I embraced being good at humanities--in part because I found amazing female role models that were largely lacking in the math faculty. (Due credit to Ms. Brigance who taught me not only Latin, but ran independent studies in Sanskrit and ancient Greek.) When it came time to think about dropping one of the AP courses from my schedule because taking so many while struggling with depression and varsity running seemed unwise, it was obvious that AP Calculus (and senior year, physics ) was on the chopping block.

In college, after avoiding all the math and science I could (with the exception of environmental studies), I wound up taking higher-level analytic and logic classes for my philosophy major; my undergraduate thesis lay at the intersection of modal logic, set theory, and philosophy of language. I found myself in rooms full of math and physics double-majors, asking about all their other classwork. I particularly admired the femme students among them and often wished I had continued on with math so I could engage more fully with their work. I occasionally longed to be in their topology class too, so I could could talk about the cross-pollinations between that and the set theory we were learning in philosophy. It was at this relatively late stage that it became clear to me: of course I could have done it! (At least through the B.A.) But nonsense from both outside and inside my own head stopped me starting in frickin 7th grade.

I am saying that I am a classic case study in social forces that cause us to have fewer female students in STEM -- and my story is one of the more positive ones! I never experienced sexual harassment or any of the associated discomfort that so often can come with being a female in male-dominated spaces. My supportive and brilliant advisor in Philosophy was male (as were my advisors in the majors I nearly completed in Classics and English). I had examples at every step of the way of brilliant femme friends who were succeeding in math and science. I had parents who encouraged me unconditionally and wanted only the best for me.

But now, even in history, I still experience occasional problems related to my gender. I continue to have "disagreements" with senior male historians who "don't believe" my numerical claims, taken straight from archival research in government sources. While sometimes it is intellectually flattering, it is often distinctly gendered when people are surprised that my 'garden history' touches on 'big' issues of political-economy, capitalism in midcentury America, and doesn't confine itself to social history topics like gender and the home. (I have talked to multiple male historians of gardens who have not shared these experiences.) I have missed out on a significant professional opportunity almost certainly because I declined a date with an influential older male historian. I have suffered from negative student feedback linked to gender.

But I'm not just complaining, I'm working to fix it. As always, I'm proud to be part of the American Society for Environmental History, actively working to tackle gender bias in its ranks, and to serve on the ASEH Committee reviewing the report on this problem (pictured left). I'm also a proud member of the Coordinating Council for Women in History and do my best to support and highlight my brilliant peers of all genders, races, ethnicities, and backgrounds.

All this is to say: screw James Dalmore, the latest New York Times article (that I refuse to link to and give hits), and anyone who claims that we need to seriously consider any arguments for biological differences in STEM aptitude, or aptitude in any human endeavor. We can have those discussions someday on the basis of good science (hopefully produced by female-identifying scientists in equal measure) only once we have removed the social barriers standing in the way of so many brilliant women, minorities, and other underrepresented groups. Prove your specious arguments by making opportunity truly equal and watching what happens. Until then, I really don't want to hear it.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed