"Only two things money can't buy

That's true love and homegrown tomatoes !"

If I's to change this life that I lead,

I'd be Johnny tomato seed...

Plant 'em in the spring; eat 'em in the summer,

All winter without 'em's a culinary bummer

I know what this country needs:

Homegrown tomatoes in every yard you see!

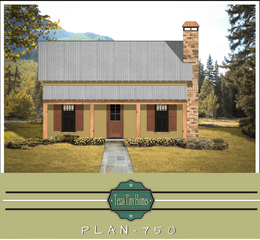

WW1 gardeners grew tomatoes too!

WW1 gardeners grew tomatoes too!

As a final illustration of the importance of tomatoes in war, please read one of my favorite historical finds EVER, straight from the Wall Street Journal at the height of the war:

'My one and only,' He cried passionately, 'come to me. Shake off the hackles that are holding you dormant, arise and let me take you in my arms. Let me display you in all your pristine glory to envious friends and passersby. Raise your head to the heavens and your face to mine, and by so doing make me the happiest, proudest, and most fortunate man in all the world. Arise, my love, arise.' |

I forget all about the sweatin' & diggin'

Everytime I go out and pick me a big one

Lack of Variety

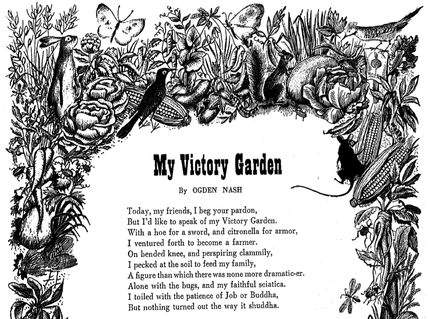

Yay Southern Exposure Seed Exchange!

Yay Southern Exposure Seed Exchange! Solution:

Next year, I’m growing many different types of tomatoes for different purposes! Green Zebras and Purple Cherokees for color, flavor, and novelty, golden pear cherries for our small ones, and then only filling in the gaps with generic slicers like Brandywine and Big Beef.

Lack of Support

Solution:

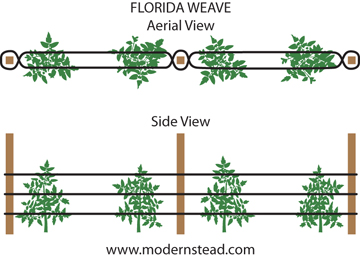

Next year I want to stake out our tomatoes the way I was taught for big rows: we’re constructing a Florida weave, or else.

This is efficient in terms of labor since no tomatoes are handled individually, orderly in appearance, and incredibly sturdy, since it relies on metal stakes pounded into the ground. It also works only in rows; this is the most pro-row you will ever see me.

Bushiness

JUNGLE.

JUNGLE. Solution:

Don’t get married at the start of the growing season next year – or leave town for a week-and-a-half for any other reasons either, I guess?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed