“Detroit?,” you say, “But I thought you studied garden history!”

From the Smithsonian's amazing Community of Gardens Project.

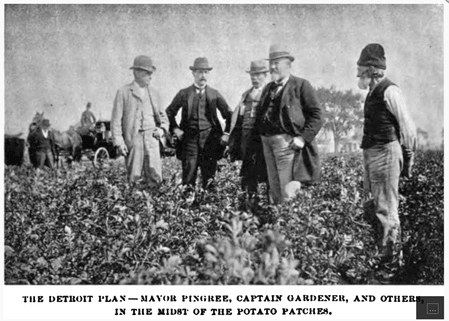

From the Smithsonian's amazing Community of Gardens Project. In short, Mayor Hazen S. Pingree of Detroit began modern urban gardening projects with a radical municipal initiative in 1893.

A former union soldier and escapee from a confederate prisoner camp in the Civil War, Pingree was a cobbler by trade. These humble origins lent credence to his self styling as a citizen-reformer committed to fighting municipal corruption when first elected Mayor in 1890.

All was going more of less well for Pingree and Detroit in the battle against bribery, when suddenly for obscure reasons linked to the gold standard, investment in Argentinian banks, and a widespread lack of calm heads, the Panic of 1893 sent the United States into a severe and rapid depression. Unemployment in Michigan leapt up to 43%, and Detroit was particularly hard-hit, as a regional center for industry and banking. Pingree was apparently destraught to see so much suffering among the unemployed, and people cried out for the municipal government to do something about it already!

[Anecdotally, protestors literally stood outside city hall chanting "Bread or Blood!"]

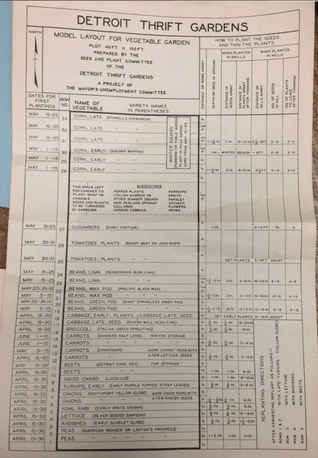

Sample garden plan from the Detroit gardening program of the 1930s. From Detroit Public Library, Burton Historical Collection, MS/Mayor’s Papers 1931, Box 6, Folder "Mayor's Unemployment--Gardens"

Sample garden plan from the Detroit gardening program of the 1930s. From Detroit Public Library, Burton Historical Collection, MS/Mayor’s Papers 1931, Box 6, Folder "Mayor's Unemployment--Gardens" - 1) Saving municipal salary dollars AND

- 2) Teaching the unemployed about moral value of hard work, of course.

- The program was patronizingly refered to as "Relief by Work" and prospective donors to the program were assured it was only the "worthy poor" would participate and benefit.

Across the city, vacant lots and unused acres of land were plowed up and divided into plots. By applying to the Mayor's office, unemployed males could secure a plot for their own use, to grow food in for their families. For many Detroiters who participated in the program, it meant the diference between their children going hungry or not. This was especially true since anyone recieving aid from the city's Poor Commission would become ineligible for said aid if they did not also sign up for and cultivate a garden plot: if you were going to get handouts, you had better do some work growing your own food to earn it.

Despite the early-Progressive-Era condescension and coercion wrapped into the program, it was a huge success in every possible sense. the first season, Pingree was able to secure 430 acres of land within city limits, which provided plots for 945 families. The citizens of Detroit who benefited from the program wrote letters to City Hall expressing their thanks (most imperfectly or illegibly, since many of them had little education). Most of the unemployed were recent German and Polish immigrants, grateful to this new Mayor and this new program. Beyond the proverbial potatoes, they grew all sorts of vegetables: beans, corn, squash, cabbage, carrots, pumpkins, beets, cucumbers, and more. The city's street sweepings were used as fertilizer, combining the garden program with city sanitation efforts. Newspapers far and wide praised "the Detroit Experiment."

(W. Adams St & Woodward Ave)

(W. Adams St & Woodward Ave) “THE IDOL OF THE PEOPLE.”

Although the 'potato patch' program was discontinued as the economy recovered, Detroit would again turn to its legacy in future times of crisis. During the Great Depression, cities across the country copied Detroit's early example in starting up what were then called 'Thrift Gardens'; in World War II, as Americans fought to protect liberty at home and abroad, Detroiters again had robust urban gardens. Not only did the city support gardens, in fact, but many war plants within and outside the booming industrial city offered garden plots on their factory campuses for workers and their families. Today, the Michigan Urban Farming Initiative again is walking in Pingree's footsteps, promoting urban gardening as a way for Detroiters to combat the ills of post-industrialization.

Far from becoming irrelevant as the years role by, and as Detroiters reading this may well know, Potato Patch Pingree’s legend persists into the twenty-first century; he was called “the greatest mayor in Detroit history” in the Detroit Free Press as recently as 2015.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed