Many World War II instructions had some variation on the following sentiment:

[One] should make every attempt to arrange with farmers, landscape gardeners, or dealers of farm equipment for plowing large areas intended for gardens by means of tractors. Some gardeners will be able to secure a team for plowing as they have in the past, but the majority of backyard gardeners will have to decide between spading or being without a garden all together. (Hans Platenius, Victory Garden Handbook, A Guide for Victory Gardeners in New York and Neighboring States ... (Ithaca, N. Y.: Cornell University Press, 1943), 11)

This tractor made quick work of tough sod I had half-heartedly tried attacking with a shovel before our neighbor intervened. Payment included cinnamon buns using America's Test Kitchen recipe.

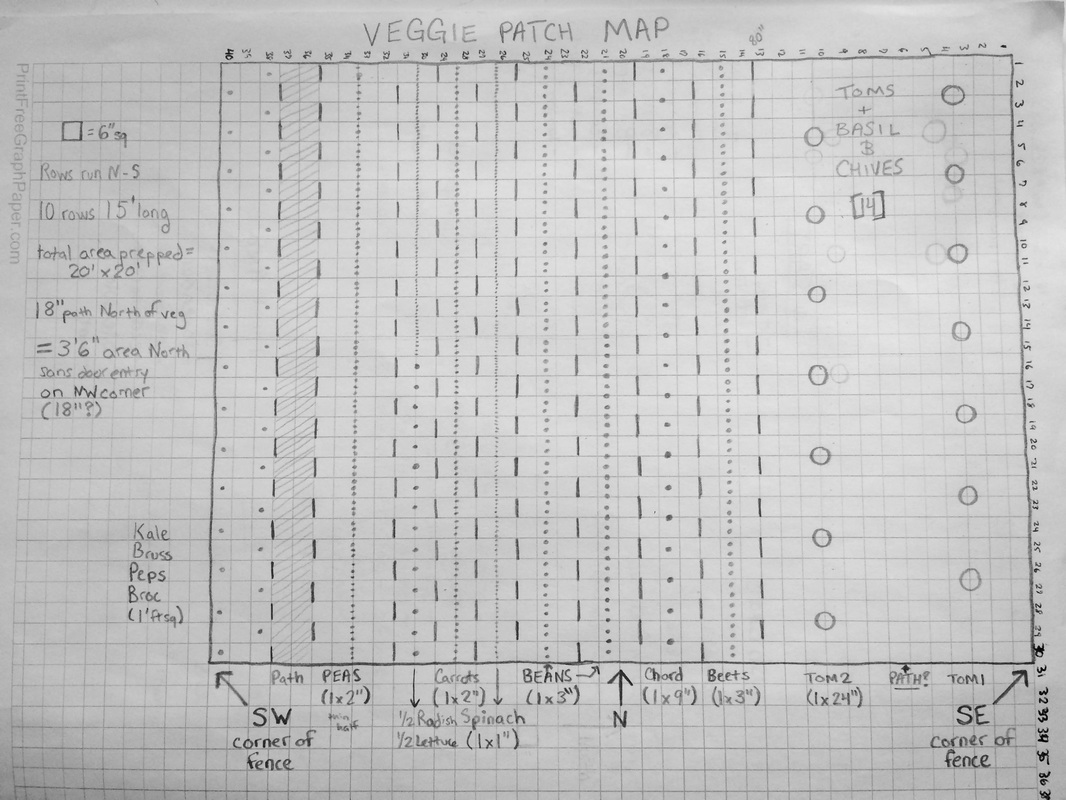

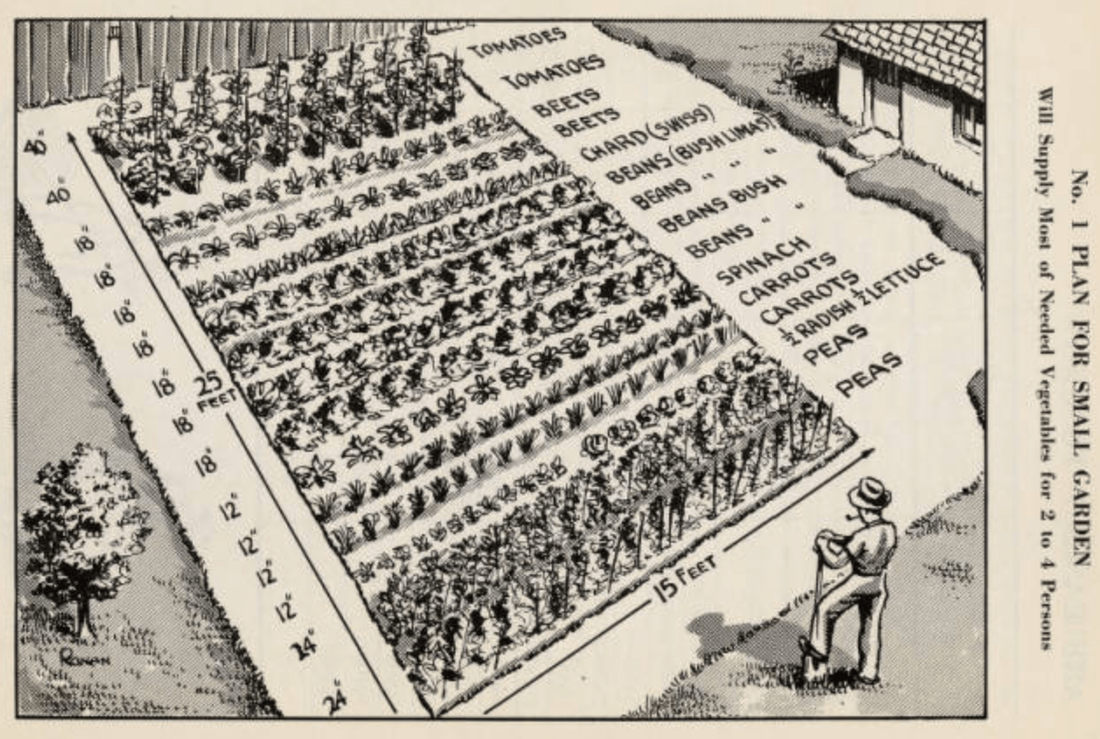

We wound up staking out a 20' by 20' square, although our plans called for 15' by 18.5'. We figured we could use the spare space for corn , and fudge-room. If growing anything more seemed too much work, sprawling vines like the squash family take up a lot of space and keep down weeds with their huge leaves. Besides, taking on as much as you think you could possibly handle--and then a little more!--is very much in the spirit of the World War II homefront.

One thing that is already driving home in this process is the reality of the amount of time committing to a full-fledged garden can take. As a graduate student, I often work well more than 40 hours a week, even if they aren't the most strenuous. On top of that, this spring I undertook to move to a new house, plan a wedding for early summer, and, as happens in life, was accosted by a number of family events outside my control that required time, energy, and emotion. Just figuring out how we are going to keep the regular lawn mowed is turning into quite the adventure , let alone raising a work-intensive garden in the middle of it. I'm increasingly inclined to follow in the steps of Mr. Aiken and follow his peculiar method of gardening described in one local newspaper from 1944:

For starts, I'm hardly alone in undergoing a move as I start my garden; during World War II, mobility for Americans hit an all-time high. People cashed in their savings to follow loved ones to the military bases where they were assigned, to find jobs in new war plants (locations ranging from the unknown Willow Run, Michigan, to already-overcrowded LA.), or took advantage of high wages and low unemployment to move out of the racist South, like many African Americans. Unlike many of those migrant workers and families, I was able to find a single-family home to rent; many people rented rooms, lived in hastily-constructed apartment complexes, or even large trailer parks for workers and military personnel and their families. (Hence this "Share Your Home" Poster, courtesy the National Archives.)

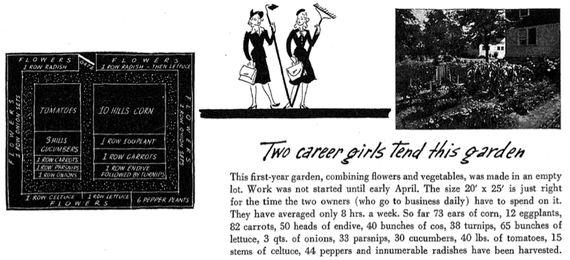

Second, work hours were increasing over the course of the war as unemployment hit functional zero by mid 1941. My summer plans sound strenuous: working 40 hours a week at Hagley's Manuscript and Archives Division (on the Sarnoff Collection!), researching and writing my dissertation in evenings and weekends, and maintaining both this garden and this blog, all while hopefully still finding time for friends, family, and occasional barbecues. On the other hand, male war workers of the era put in an estimated average of 46.9 hours a week, many with commutes lengthened by relying on insufficient public transportation, walking, or biking in an age of rationed gas and tires. They were expected not only to grow gardens, but to volunteer for a variety of other patriotic drives each of which chipped away at time for leisure and relaxation. And at the end of those long days, they had no Netflix to console them. History's #1 lesson strikes again: no matter how much you might whine about today, the past was never really better.

Finally, my wedding plans -- although a tad more involved than your average courthouse war wedding -- are another surprisingly accurate feature of my summer experiment. The marriage rate in the U.S. skyrocketed to almost triple the rates today, and 50% higher than in 1940, before the U.S. entered the war -- check out this great chart with awesome editorial from The Washington Post. More about historicizing my own white wedding later, though.

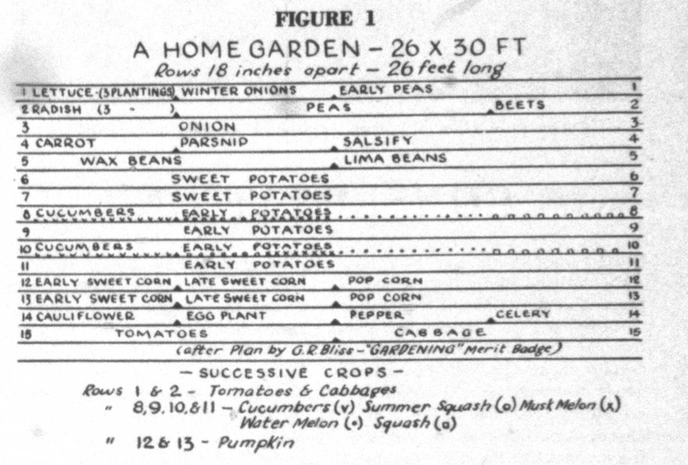

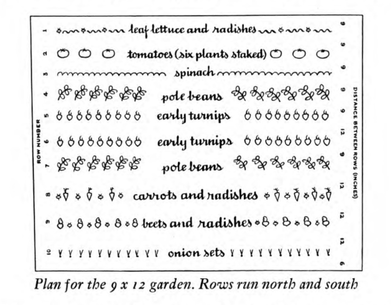

All these time-sinks aside, as it stands I have now have a patch of land, and a plan:

RSS Feed

RSS Feed