ANASTASIA DAY TO SERVE AS SMITHSONIAN FELLOW IN WASHINGTON D.C

Anastasia Day is off to do a Fellowship at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History!

| [In my award package, the Smithsonian was kind enough to include an outline and instructions for a press release to announce the good news -- here is what I did with it. Welcome to my first press release!] |

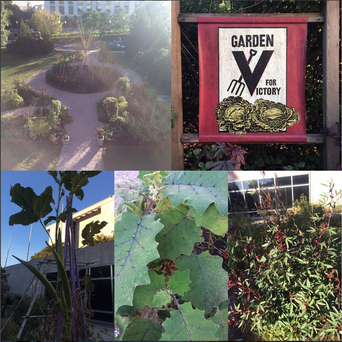

NMAH Victory Garden, Fall 2016

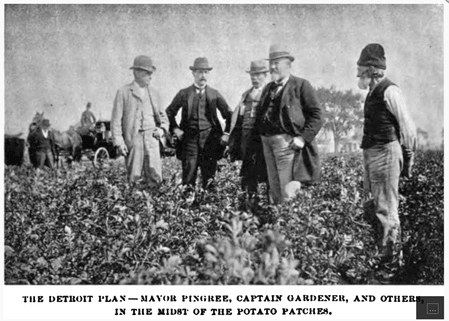

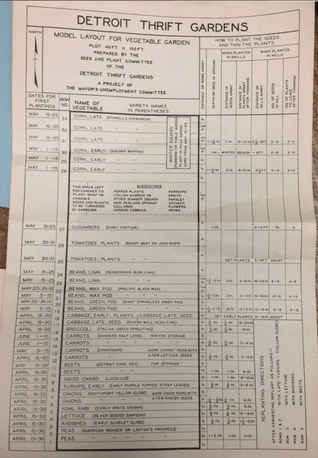

NMAH Victory Garden, Fall 2016 Anastasia’s project is an analysis of World War II home front victory gardens in light of developments in agriculture, industry, and society. In 1943, over 21 million of these small vegetable plots produced over 40% of Americans’ fresh produce. Up to two-thirds of citizens participated, making victory gardening the most successful local food movement in U.S. history. Popular memory cites victory gardens as inspiration for sustainable, grassroots food activism today, but her scholarship focuses on factory metaphors of industrial production within this movement. While at the Smithsonian, she plans to consult such archival collections as the Warshaw Collection of Business Ephemera, the records of the War Production Board, The Princeton University Poster Collection, the Pete Claussen Collection of American Flag Magazine Covers, and also the Smithsonian’s own history of interpreting victory gardens in the longstanding “Within These Walls” exhibit on the U.S. World War II home front experience.

In the long run, Anastasia seeks to publish this project as a book aimed at both public and academic audiences. Examining World War II victory gardens, the most successful local food movement in American history, can provide valuable lessons for the future, she argues – and not only for growing sustainable food systems, but thinking about the relationship between state and society, between government and business, and between food and the environment in American culture.

The Smithsonian Institution is the world’s largest museum and research complex, with 19 museums and galleries and the National Zoological Park. On July 1, 1836, Congress accepted the legacy bequeathed to the nation by James Smithson and pledged the faith of the United States to the charitable trust. The total number of objects, works of art and specimens at the Smithsonian is estimated at nearly 138 million, including more than 127 million specimens and artifacts at the National Museum of Natural History. Smithsonian Institution Fellows are key to the Smithsonian’s aspiration to discover, create, innovate and diversify. The Smithsonian’s vast collections, numerous facilities, and staff expertise provide an incredible range of opportunities for independent research. Smithsonian Institution Fellows receive stipends from the central fund and can be found in all areas of the Smithsonian exploring, probing and charting new directions.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed