Pre-Trial Context:

"Make the rows straight. A good garden line is as necessary as any garden tool.”

-John A. Andrew, Kitchen Garden Guide (Philadelphia, Pa: Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, 1942),

The Case For Rows

- An orderly, tidy, leisurely, and all-American aesthetic. I'll let the quote to the right speak for itself. [Leonard Harman Robbins, “15,000,000 Victory Gardens,” New York Times Magazine, August 23, 1942.]

Rows from Putnam &Cosper

Rows from Putnam &Cosper - Easy weeding and maintenance, they said. Over and over again I read variations on the sentiment: "Straight Rows Aid Cultivation" [Victor H Ries and Ohio Fuel Gas Company. Home Service Dept, Planning the Victory Garden. (Columbus, Ohio. Home Service Department, Ohio Fuel Gas Company, 1944) 5]. When your garden plants are in rows, by necessity your weeds will grow in between them, also in rows, and are therefore easier to identify, and eliminate, moving down the row either pulling my hand or using a cultivator tool. Furthermore, one should always pursue the fewest, longest rows to maximize gains here: "One long row instead of two short ones saves labor." [Joseph H. Boyd and Victor H Ries, Garden For Victory, Ohio, Bulletin 232 (Columbus, Ohio: Agricultural Extension Service, Ohio State University, 1943),

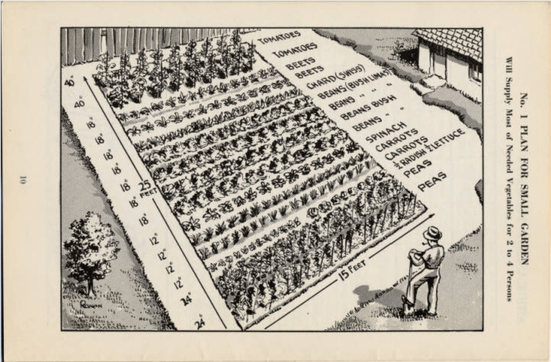

- Making the most of the space you’ve set aside for gardening: good row garden layouts help the gardener "plan to make every square foot of your available land account for itself in the greatest number of bone and tissue building elements," wrote J. G. Alexander (“Your Victory Vitamin Garden,” Hygeia, June 1943.) Close rows = more product per ft., according to all the World War II experts.

- Rows lend themselves to more variety in a small garden than over-large patches of any given crop. You can even split rows half-way down, as we did with the radish/lettuce row. In the middle of explaining why one should follow their row plan, Sunset Magazine's Vegetable Garden Guide explains: (1942, Full view)

Ibid.

Ibid. - Fewer pests because less concentrations of any one plant over a wide and long area. If monocultures breed pest specialization and increase populations, more plant diversity decreases pest propagation -- and, at least on the cross-ways axis, rows create much diversity. Essentially, if intercropping two species in a field is putting two rows of different plants side by side, a row garden with one row of each plant would be considered maximum intercropping if it were happening over acres and acres . . . so we should have minimum pest problems, right???

- Ease of access for harvesting even small beans – no reaching across over-wide garden beds. (Even four feet can be way too wide if you are under 6 feet tall, as I have discovered in past garden plots.) With bed layouts, if you lean on the soil, you are inevitably compressing the roots or possibly squashing plants. Rows seemed initially like they could fix this problem; although there weren't any rows, there would be logical foot-places between the rows that would facilitate access, or thus ran my very early hopes.

The Verdict on the Case

Having ripped out the overgrown beans, the tomatoes sprawl where beets and chard were meant to thrive...

Having ripped out the overgrown beans, the tomatoes sprawl where beets and chard were meant to thrive... In all fairness, it might not be that rows are inherently flawed; it could simply be that the plan I chose to follow was bupkis in terms of spacing. Certain rows were COMPLETELY overshadowed by their neighbors. The beans in particular just took over all the adjacent areas to their own space and completely eliminated the path between them; you couldn’t tell they were in two rows within two weeks of sprouting! The chard didn't stand a chance -- the bugs that seemed to originate with the beans also migrated to eating chard as the season went on, so the diversity failed to save them!

[NOTA BENE Let it not be thought that I am denying any human error at play. Perhaps the beets might have stood a chance of surviving on their own if only we had chosen a more sturdy staking method than wire tomato cages. It became clear the cages were incapable of supporting the great bulk of weight presented by all the fruit, and the tomato plants swallowed the beets alive as they spread out horizontally as the summer went on . . . . The plan likely assumed we would be competent at staking our tomatoes so they could grow in a more, erm, vertical direction.]

Nonetheless, perhaps the unknown author of my garden plan should have followed Jean-Marie Putnam and Lloyd C. Cosper when they advised gardeners of 1942 to invest in some technology to aid with planting:

"Garden-o-meters show the proper distance apart the rows should be for each type of plant." – pg 52, Gardens for Victory, First (New York, N.Y.: Harcourt, Brace, and Company, 1942). [This is most certainly NOT what Putnam and Cosper were referring to, but this was the first google image result for "gardenometer" .... however, when unable to find any "garden-o-meters" online, my first thought was not dissimilar. I immediately went to an article I had just read on singularityhub.com entitled: "FarmBot Will Grow Your Food For You; Just Press Go" . . . god, I really should write a post about farming-futurism sometime . . . ] |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed