The Book

Leo Marx was an early scholar in American studies -- working from the basis of U.S. exceptionalism and looking to explain unique traits of the American experience and national character. This book was based on his 1950 dissertation in the History of American Civilization, completed at Harvard.

His source base is limited primarily to the literature produced by 'great' (read: white, male) authors of the American cannon. Washington Irving's Sleepy Hollow, The Tempest ('Shakespeare's American Fable'), the agrarian writings of Thomas Jefferson, the technological visions of Tench Cox, and bits of Emerson, Thoreau, Twain, Hawthorne, Melville, and many more appear.

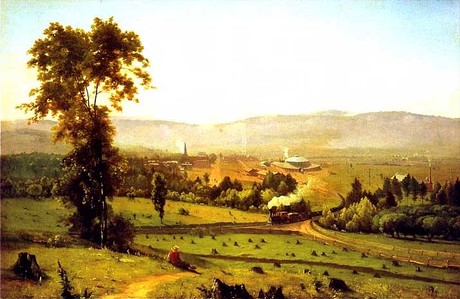

Through these disparate authors, Marx identifies a unique and persistent trope: these authors, in grappling with the onset of American industrial power, locate a tension between nature and culture in the form of, well, a machine in the garden. In his own words:

[Throughout the American cannon,] the machine is made to appear with startling suddenness. [...] The ominous sounds of of machines, like the sound of the steamboat bearing down on the raft or of the train breaking in on the idyll at Walden, reverberate endlessly in our literature. (15-16)

The distinctive attribute of the new order is its technological power, a power that does not remain confined to the traditional boundaries of the city. It is the centrifugal force that threatens to break down, one and for all, the conventional contrast between these two styles of life [pastoral and urban]. (32)

These works manage to qualify, or call into question, or bring irony to bear against the illusion of peace and harmony in a green pasture. (25) [...] To change the situation we require new symbols of possibility, and although the creation of those symbols is in some measure the responsibility of the artists, it is in greater measure the responsibility of society. (365)

The Garden

Detail, Jane Peterson, 'Turkish Fountain with Garden,' ca. 1910, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Detail, Jane Peterson, 'Turkish Fountain with Garden,' ca. 1910, Metropolitan Museum of Art - Location -- It is tempting to state that a garden constitutes plants that are grown at or near the home, while agriculture is out in fields. How then, however, to explain public gardens? Botanical gardens? Community gardens? While certainly gardening and domesticity are entwined in certain times and places of American history, the connection is not definitive.

- Function -- Gardens can be healing, as seen in the growing gardens for veterans movement, hospital gardens, and the growing field of horticultural therapy. Gardens can also be aesthetic and artistic places, as the American Impressionist painters conveyed in oils -- see The Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts online exhibit, The Artists' Garden. Gardens can be public and educational, as the mission statement of the famed St. Louis Botanical Garden illustrates. Or they can be privately cultivated in food deserts where that may be the best way to ensure nutritional, fresh, meals for your family; such gardens grow social justice as well as vegetables. Some gardens, like Victory Gardens, are highly political and patriotic. However, there are no strict rules: gardens can serve multiple of these functions or other ones entirely.

- Relationship to the market -- When thinking specifically about how to differentiate gardens from agriculture, an easy answer might seem to be that agriculture is done for a living, to produce commodities that sell on the market for profit, while gardens remain outside the commercial sphere. However, this doesn't hold either. What about public gardens who charge for admission? Or what about truck/market gardens? How about the ways that gardens play into domestic economy by saving money on food? They may not enter the marketplace, but they are still shaped in relation to it.

As much as the garden is a construction, it is also, undeniably, a place. Gardens are material and real. They have plants, with roots in the soil and leaves angling for sunlight. One can sit there and think, and write. This summer, that is what I intend to do: a historian in her garden.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed