Charles Alston

From the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

From the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Perhaps Alston's most famous artwork is his 1970 bust of Martin Luther King, Jr. When it was installed in the White House in 1990, it became the first representation of an African American to be put in the White House, over a century after the abolition of slavery and just under 500 years after the first enslaved peoples were brought from Africa to 'The New World' in 1501. The Smithsonian Magazine has wrote great article about the bust yesterday, as an original casting joined the collection of the new Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

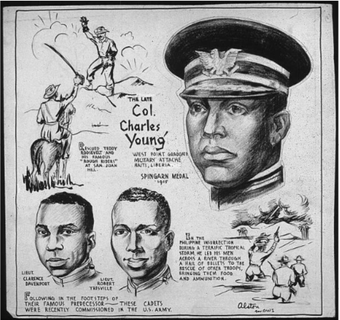

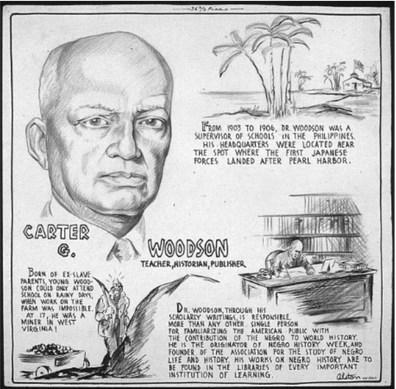

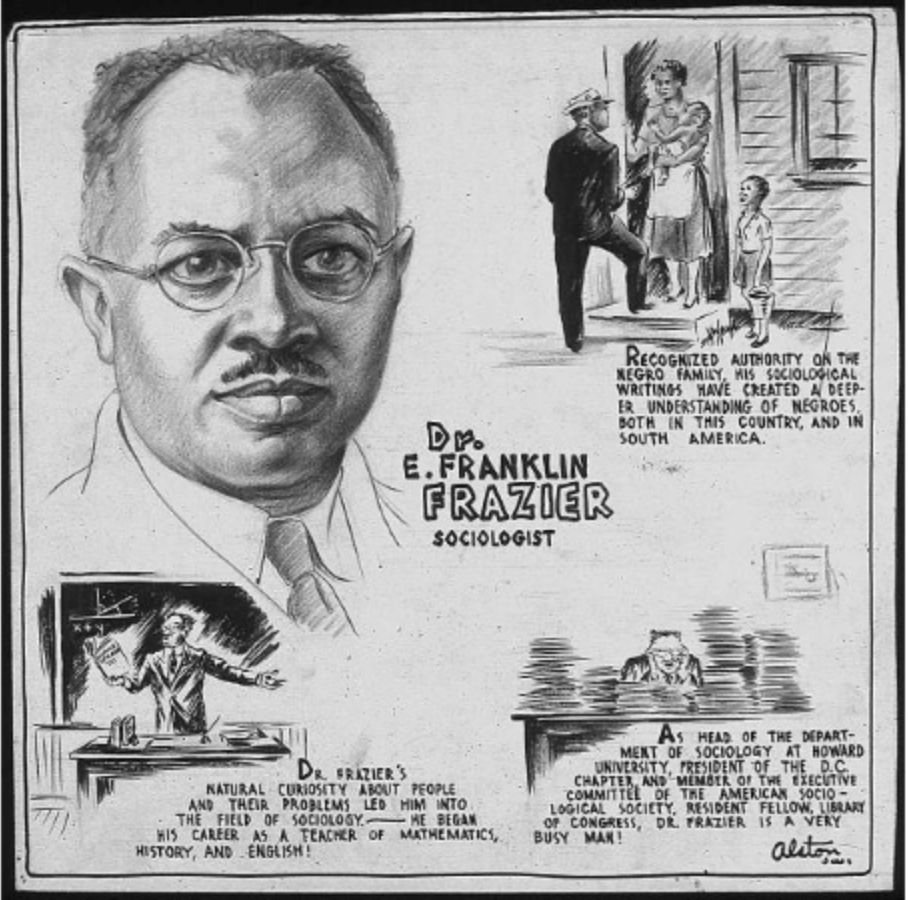

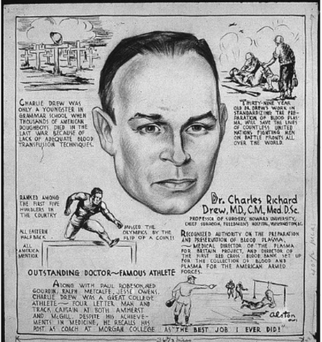

These images all come from the Alston collection Artworks and Mockups for Cartoons Promoting the War Effort and Original Sketches by Charles Alston, ca. 1942 - ca. 1945, now stored at the National Archives, College Park, MD. You can see browse through the complete digitized collection through the everyday miracle of the internet, and the tireless efforts of librarians, archivists, and others to bring these collections to the public at the click of a button.

Throughout this article, all images and names link to a larger version of the cartoon on the National Archives website.

World War II Cartoons

Alston's cartoons clearly grapple with the difficulty of the task before him; he never hid or obscured America's ugly racial past, often including references to slavery. However, he focused on the accomplishments and achievements of blacks in the war -- and sought to frame them as part of a long and continuing tradition of selfless sacrifice and crucial contributions to the nation from the black community. Alston believed firmly in the power of history, and in the power of the press, where his cartoons were published.

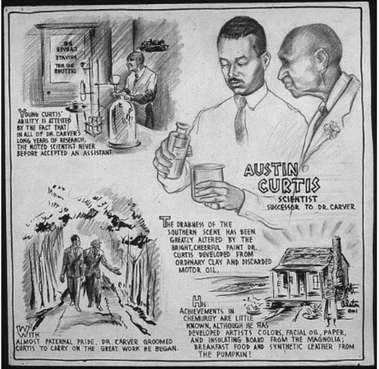

The largest group of Alston's cartoons is a series of biographical sketches of black Americans, naming their accomplishments and linking their efforts to the success of the United States in war and in peace. While he included such canonical black Americans as reformer Frederick Douglas and scientist Dr. George Washington Carver, he was careful in his couching of them. He painted Douglas in patriotic hues by mentioning the Liberty Boat named after him currently fighting the Axis powers, even while noting that both had been born into slavery.

Most importantly, though, Alston also gestured to lesser-known black Americans, such as Austin Curtis, 'successor' to Dr. Carver. [see cartoon above]

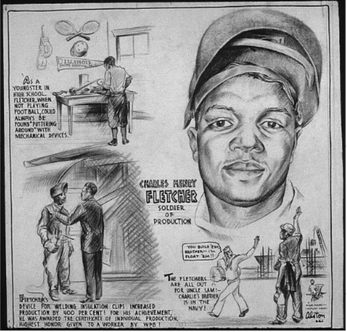

More surprising, then, is Alston's single cartoon acclaiming a factory worker on the assembly line in the home front war: Charles H. Fletcher - Soldier of Production. While the martial framing of Fletcher as a soldier played into rhetorics of sacrifice in war, another link between the army and the factory in World War II is that both were struggling with race relations. In the shortage of war workers, doors to high-paying jobs and work were open to black americans that hadn't been previously -- much to the anger of certain unions, employers, and Americans. In industrial Detroit, these tensions exploded in the Race Riots of 1943; at the height of World War II, 6,000 federal troops were called out to stop the rioting. Emphasizing the patriotic contributions and value of a black worker might have been Alston's subtle response.

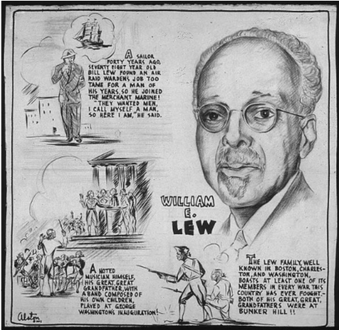

Alston did not confine himself to World War II combatants -- not content to merely gesture toward black service to the nation in the present, he set out to document black military service throughout United States history. The epitome of this trend can be seen in his sketch of William E. Lew, who not only joined the merchant marines at age 78 during the Second World War, but whose family history of service stretched back to Bunker Hill and George Washington's inauguration!

He also drew a cartoon illustrating Robert Smalls, a black hero of the Civil War who, while piloting a Confederate transport ship, defected along with crew and cargo to the Union Cause.

In looking to the past of black military service, Alston also offered correctives to white mainstream histories of the time, and even myths that still persist today. Once instance of this is in his pointed depiction of Col. Charles Young, a West Point graduate who, in fact, RESCUED Theodore Roosevelt and his famous "Rough Riders" at San Juan Hill -- a key element of the story overlooked in Teddy's popular and celebratory boasts of his all-white soldiers' bravery -- and not mentioned when the future president won the Medal of Honor for his charge. (Which incidentally, was really up the un-romantically-named Kettle Hill.) Read more about Charles Young here.

[Down with the cult of Teddy Roosevelt!]

Closing Thoughts

However, even in his drive to document overlooked black Americans, Alston only included two women in his series -- Lieut. Willa Brown [left] and Bessye J. Bearden ["Club Woman, Social Worker"].

On Martin Luther King, Jr. Day, as we celebrate a day named for one inspirational and exceptional American, let us not forget all the countless other visionaries, artists, intellectuals, doctors, lawyers, athletes, architects, patriots, workers, and protestors of color who built this nation and continue to work to making it a better, more just, and more free society. Who are we not thinking of? Whose history are we forgetting, and in so doing, considering unimportant?

Further Information:

Wardlaw, Alvia J. Charles Alston. San Francisco: Pomegranate, 2007. (Find it at your local library!)

Digital Public Library of America holdings related to Charles Alston. More photographs, images of his murals, paintings, and other artworks, and more.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed